THE “FALL” OF ROME: PART I - ANATOMY OF A FALL

Hard to tell if this is a scene of Greek or Roman ruin. Since it's AI-generated, though, I'll designate it as Roman. I will not be taking questions.

The question I get asked most frequently is some variation of, “Why did Rome fall?” Recently, my young friend Caroline E. phrased the question a bit differently: Did the Roman Empire collapse on itself? I responded that, in a significant sense, yes, it did — but both the question and the answer are complicated. Her question inspired me to write these posts to shed light on the topic.

“The Fall of Rome” is a deeply ingrained concept in Western thought, warranting title case when written, much like “The Great Depression.” It is often seen as a cautionary tale about civilizational collapse, particularly in relation to modern times. We use the term freely — recklessly, even — but “fall” and “Rome” can be interpreted in various ways. I want to suggest some interpretations of those terms by addressing two key questions: What contributed to the so-called fall? And what did “Rome” even mean? Finally, I will apply these observations to the question: Are we next?

If you ask a search engine when Rome fell, you’ll likely get this answer: 476 AD. Romulus Augustulus was an adolescent, probably around 14 years old when his father Orestes installed him on the throne the year prior. Orestes held the title of magister militum of the Western Empire, a powerful position, second only to the emperor, which commanded the military. Augustulus was a figurehead, a proxy that Orestes could use while he handled martial affairs. The young emperor shared his praenomen (first name) with Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome. However, his cognomen (nickname) was less flattering. While it refers to Caesar Augustus, the -ulus suffix turns it into a mocking insult: Who does this kid think he is? Caesar?

Augustulus was deposed by the Gothic king Odoacer who had been a powerful figure in the West for some time and had just overthrown the previous emperor, Julius Nepos. Odoacer declared himself King of Italy and sent the royal vestments to the Eastern emperor Zeno in Constantinople. Odoacer didn’t consider this a revolt against Rome; rather, he pledged his loyalty to Zeno as a vassal of the East and saw little value in maintaining an emperor for the West. While Zeno still recognized the deposed Nepos, the change was irreversible – the role of Western Emperor was effectively eliminated.

While almost all deposed emperors met a violent end, Augustulus was fortunate. Odoacer sent him into exile and provided him a healthy lifetime stipend.

It's disingenuous to include all these AI-generated images of Roman destruction, because when Rome "fell," it didn't really go down like this. But they're pretty cool, regardless.

So, at this point, there’s no Western Emperor. This must mean Rome is up in flames, centuries-old institutions are crumbling, and refugees are pouring out of the Empire.

Nothing of the sort. In fact, except for those present at the deposition and whomever they told, the citizens of the Empire would be unaware their time was up. The sun rose the next day, and life went on.

However, it’s essential to acknowledge that the Roman Empire in 476 AD was greatly diminished from its height in the 2nd century AD. That period marked the Pax Romana, a hundred years of prosperity and relative calm within the Empire. It’s worth noting that pax didn’t mean ‘peace’ as we understand it today. Rather, it implied something more akin to ‘pacification,’ which has a much more militaristic connotation. There were few wars during that time because Rome brutally and swiftly crushed any uprisings. This lack of unrest, therefore, constituted peace.

What, then, were some of the challenges facing Rome in the 5th century?

Size

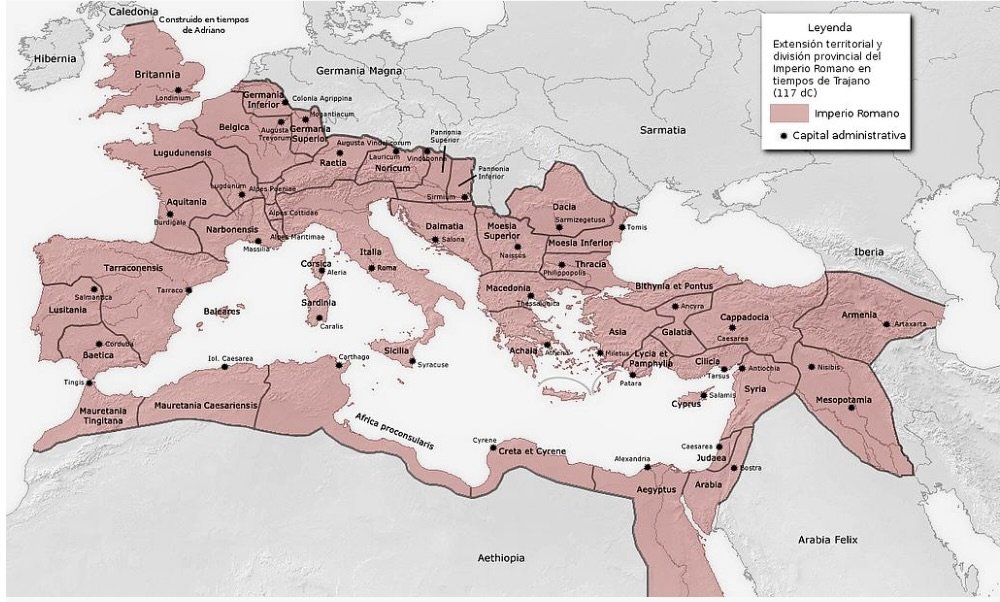

Rome reached its greatest geographic extent under Emperor Trajan around 117 AD. After his death that year, Emperor Hadrian made the strategic decision to return some of the recently conquered parts of Mesopotamia to their inhabitants, stabilizing the Empire’s borders. Though shrewd, this move was unpopular and, to many, an insult to the gods. Terminus was the god of boundaries and Roman tradition had it that once a boundary had been extended, it offended Terminus to retract it. Hadrian risked this sacrilege because he understood that the Empire had simply grown too large to be administered effectively. It wasn’t just the city of Rome or even Western Europe anymore.

Map of the Roman Empire at its greatest extent in the early 2nd century AD.

Using modern-day country references, the Empire spanned from the border of Britain and Scotland in the North to the northern edge of the Sahara Desert in the South, and from Portugal in the West to parts of Iraq in the East. It was the largest land empire in history until the Mongol Empire surpassed it in the Middle Ages.

However, such a wide geographic extent posed significant problems in ancient times. The fastest a message could travel on land was the speed of a horse. For instance, if a message needed to get from Britain to Syria, it had to cover 2,500 miles. Even with a relay system of fast horses, this journey would take several months. Double that time if Britain required a reply from Syria. It’s easy to see how information could become outdated, rendering responses irrelevant over such an extended timeframe and wasting valuable resources.

Division

In the 3rd century AD, the emperor Diocletian divided the Roman Empire into East and West. Each of these administrative districts was governed by an Augustus and a lower-ranking Caesar. The Caesar, though junior, wielded the same power as the Augustus, except the Augustus had the final say in any matters of contention. This arrangement was known as the tetrarchy, meaning “rule of four,” and had many benefits. It ensured faster responses to threats; it freed up emperors to focus on their specific regions; and it secured dynastic succession by designating the Caesar as heir presumptive. It functioned well … for a moment. However, personal ambition among the 4 rulers soon led to conflicts. Ultimately, Constantine the Great emerged as the last man standing after defeating several other tetrarchs in a series of civil wars.

By 476 AD, the tetrarchy was a distant memory, and the Empire had solidified into two distinct halves: West and East. The Western Empire, which we are most familiar with, included Europe and North Africa, but at this point, Rome commanded only a fraction of that territory. The Anglo-Saxons controlled England, the Visigoths held Spain and France, the Sueves occupied Portugal, and the Vandals ruled North Africa. Additionally, the Ostrogoths, Burgundians, Basques, and Cepids had small holdings throughout the region, leaving Rome with authority only over Italy and parts of the Balkans.

Despite its diminished status, the West aspired to regain its lost territories and mounted numerous campaigns to retake control, with varying degrees of success. Throughout the 4th and 5th centuries, lands changed hands multiple times, and by the end of the 5th century, the Western effort at reconquest was struggling. Among other challenges, the West faced a severe shortage of manpower and resources. Military roles had been outsourced to the Goths and other Germanic tribes, whose loyalty was always uncertain. As territory was lost, both potential recruits and tax revenues plummeted, making it seem as though the West was on the ropes.

Yet, life continued as normal for most Romans. How do we reconcile these conflicting images? More on that later.

Germanic Tribes

The Germanic invasions, which had been a persistent thorn in Rome’s side throughout most of its history, had a significant impact primarily through the loss of territory. This territorial decline prompted waves of people from north of the Danube to flood into the Empire, both East and West. In most cases, these groups did not aim to conquer Rome; rather, they sought a place to settle. Early in the 5th century, the encroaching Huns drove hundreds, of thousands of these so-called “barbarians” to seek refuge within the Empire. While Rome ultimately repelled the Huns, the influx of migrants had already begun. These tribes spread throughout Western Europe, and notably, those which settled retained Roman institutions, establishing their own bureaucracies, Senates, and even emperors (or kings).

Political Instability and Corruption

The Crisis of the Third Century is a modern term used to describe the mid-to-late 200s when Rome teetered on the brink of collapse. The challenges were overwhelming: Germanic tribes continued their encroachment from north of the Danube River, while the Sassanids in modern Iraq launched several invasions of the Eastern Empire. The economy was in shambles due to rampant inflation, exacerbated by the repeated debasement of coinage, which reduced the percentage of precious metal. Unfortunately, the Romans’ response to these crises was woefully inadequate. A revolving door of incompetent emperors, most of whom were military leaders, resulted in short reigns marked by usurpation and assassination. These civil wars severely undermined the Empire’s ability to confront the myriad challenges it faced. Although a series of Illyrian emperors (from roughly modern Croatia) eventually brought Rome back from the brink, the Crisis inflicted lasting damage on the economy, the populace’s faith in institutions, and the Roman psyche.

After eliminating his fellow tetrarchs, Constantine the Great administered the Empire effectively in the early 4th century. Despite the usual challenges, competent administration continued, sometimes flourishing and sometimes faltering, until the 5th century. By this time, however, a succession of incompetent emperors occupied the throne, including perhaps the worst of all, Honorius. Detached, dispassionate, and prone to making colossally bad decisions when he did engage, Honorius stood by as the West fell into decay during his excruciatingly long 30-year reign.

Honorius was arguably the most useless ruler in Rome's long history. He cared far more for his pet birds, particularly the chickens, than he did for the vast empire he ruled. His neglect caused irreparable damage.

Corruption was rampant in the 5th century, particularly among military leaders. Officers often used cash payouts to bribe their troops, who in turn bribed their superiors for promotions. This practice diminished the meritocratic nature of military advancement and deprived the army of the best candidates for leadership. Consequently, paid loyalty became a commodity, corroding the military’s effectiveness and leading to an overreliance on Germanic tribesmen to fill army roles. As previously mentioned, these soldiers were not particularly loyal and were prone to revolt in favor of their kinsmen who were pouring into the Empire. Additionally, generals gained outsized power and clashed with one another in a series of devastating civil wars.

Corruption extended beyond the military. The bloated governmental bureaucracy was characterized by inefficiency, extortion, and graft. Provincial governors squeezed their populations for money, leading to widespread suffering and disillusionment among citizens. This resentment eroded the cohesion that had once bound the Empire through the ideals of honor and sacrifice inherent in “Romanness.”

Decline of Civic Virtue

The late 5th century was characterized by self-interest, apathy, and an erosion of traditional values. In 212 AD, Emperor Caracalla extended citizenship to every free man in the Empire, granting substantial benefits to as many as 30 million people. This remains arguably the largest grant of citizenship in world history. The motivations behind his decision are unclear and poorly documented; some speculate it was to increase revenue. However, as most of these new citizens were low-level workers or subsistence farmers, it’s unlikely they contributed significantly to the Empire’s income. Regardless of his intentions, Caracalla’s move diluted the population that identified with the ideals of Rome and understood what it meant to be a Roman, further damaging the concept of Romanness.

At the same time, while Christianity possessed its own moral code, its emphasis on pacifism ran counter to the martial spirit that had characterized and united Rome prior. This shift further eroded the bonds that had long held the Empire together, though it would later be the binding force for a new idea of Romanness.

Civil Wars

For centuries, Romans killed other Romans by the thousands, depleting the pool of recruits across the Empire. By the 5th century, a term of military service lasted 25 years, and the odds of surviving until retirement were roughly 50/50—not a compelling incentive to join the military. This grim reality prompted many to escape conscription by any means necessary. However, for those who did serve, charismatic or commanding generals could secure the loyalty of their troops, often leading them to declare their commander as emperor. This relationship, perfected by Julius Caesar during his Gallic Wars in the 1st century BC, meant that soldiers showed more allegiance to their generals than to the state. A usurper could also proclaim himself emperor and enjoy the title for several months before news spread and someone finally acted against him, if they acted at all.

Hey AI: show me a turtle in some Roman ruins. Why not?

Climactic Impacts

The Roman Warm Period, spanning roughly 250 BC to 150 AD, was characterized by relatively stable and warm weather which supported high agricultural output. This fueled Rome’s rapid growth. However, by the late 2nd century, the climate began to cool and become more unstable, leading to excessive rainfall in some areas while others experienced drought. This instability devastated crop yields and severely impacted food security, particularly since the Empire relied heavily on grain imports from especially hard-hit North Africa. This climatic shift began the desertification of that region, a process that continues today.

Atilla, leader of the Huns and the so-called "Scourge of God." Why the long face, Atilla?

Throughout the Empire, food shortages led to famine, further weakening the population. They also caused runaway inflation, a concept the Romans did not understand well enough to address effectively.

Complicating these issues was the westward migration of an apocalyptic group of warriors and their families known as the Huns. Displacing countless Germanic tribes fleeing their ruthlessness, the Hunnic migrations were likely sparked in part by climate shifts on the Eurasian steppe in the 4th and 5th centuries, which diminished the grasslands that sustained their livestock which were vital for food, clothing, and transportation.

Economic Instability

The Roman economy faced relentless challenges in the 5th century. In addition to runaway inflation, the Senate indulged in lavish spending on games and entertainments. These “bread and circuses” were designed to placate the masses and distract them from the Empire’s myriad problems. However, in doing so, the government overlooked more pressing economic issues.

As is common with governments, the Romans turned to taxation to cover various, often sybaritic, expenses. Yet those best positioned to pay were also the most adept at evading their obligations, frequently resorting to bribery. When the affluent withheld their fair share, the burden shifted onto those least able to pay, widening economic inequality. Frequent civil wars and invasions exacerbated the situation, further depressing trade and destabilizing the economy.

Plague & Disease

Depressing, if AI-generated, depiction of a kid with measles, a possible cause of the 2nd century Antonine Plague.

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries, Rome endured a devastating one-two punch from plagues. The Antonine Plague, likely smallpox or measles, ravaged the Empire and killed up to a third of the population. This catastrophic loss weakened the labor force, diminished the military, and devastated agricultural production. The psychological toll was immense, and the plague was likely responsible for the deaths of Marcus Aurelius’ co-emperor Varus and possibly Aurelius himself.

The Cyprian Plague, named after the Christian bishop who first documented its effects, emerged in the 3rd century. Scholars debate the cause, with smallpox and influenza cited as potential agents. More horrifically, some suggest it could have been a viral hemorrhagic fever like Ebola. At its peak, the Cyprian Plague claimed the lives of 5,000 people a day in Rome alone.

Although these two events occurred long before the end of the Western Empire, their effects rippled through the subsequent centuries. Recurring outbreaks became a grim reality, exacerbated by overcrowding and poor sanitation, which were never effectively addressed in the wake of these epidemics. The Romans’ continued inability to understand disease causation, transmission, or treatment rendered the state helpless to prevent the death of literally millions. Food shortages left many Romans with weakened immune systems resulting in more infections and devastating effects from diseases.

In 476 AD, I doubt there were any domes like the one depicted here, but play along with me as I use the hell out of my 1-month license of AI-generated images.

The waves of plague and disease decimated the population, resulting in a catastrophic drop in production. This delayed or hindered vital infrastructure projects and adversely affected the military’s capacity to respond to emerging threats. This disruption fostered a sense of fatalism and moral decay among many Romans; some thought, “we’re doomed anyway, why not party?” Social cohesion eroded and unrest followed as the population sought scapegoats such as Jews, foreigners, or Christians. Pagan Romans, still the overwhelming majority at this time, felt abandoned by their gods, and many cited the monotheistic Christians’ refusal to worship Rome’s pantheon as the cause of the empire’s misfortunes.

***

As we can see, Rome faced unprecedented challenges which struck at the core of its political, military and economic foundations. In Part II, we’ll look at the term “Rome,” trying to understand what that meant in the 4th and 5th centuries and how it endured and overcame the many challenges outlined above.